RSV Immunizations Are Coming. This U of T Researcher Is Helping Parents Prepare

July 5/2023

By Ishani Nath

RSV researchers have been waiting for this moment for decades. Two new ways to protect children from respiratory syncytial virus, better known as RSV, are on the verge of becoming available in Canada.

Even though the majority of children will get infected by age 2, “most parents do not know about RSV,” says Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases member and Dalla Lana School of Public Health Assistant Professor Tiffany Fitzpatrick. She’s heard from parents who only learned about the virus — which has a similar seasonal pattern to the flu and symptoms like coughing, wheezing, and fever— after their child caught it. Although most cases are mild, RSV can lead to more severe illness like pneumonia, and is the leading cause of infant hospitalization in Canada and many other countries.

Health Canada is in the process of approving more immunization options to protect children against RSV— an antibody-based drug that may eventually be used to protect all newborns from severe RSV illness and a vaccine for pregnant people that would pass protection from parent to newborn. The potential impact of these new options, both for the health of Canadians and an already overburdened healthcare system, is massive.

“This could be really revolutionary,” says Fitzpatrick, who is also a scientist at Public Health Ontario. That is, as long as parents have the information necessary to make an informed decision about vaccination and understand the severity of RSV — a task that Fitzpatrick plans to address with her research recently funded by the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN).

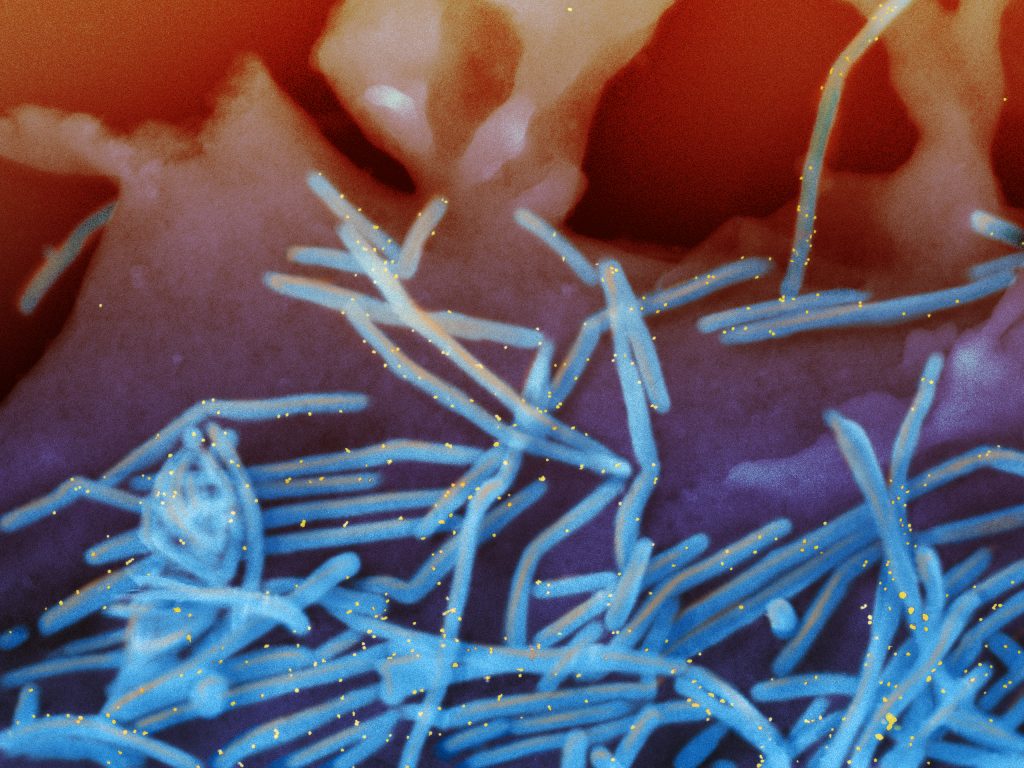

Human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (Photo: NIAID)

New RSV immunization options coming to Canada

The new RSV prevention drug and vaccine have been a long time coming. Despite more than 60 years of research, options for protecting vulnerable populations, like newborns, against the virus remained limited — until now.

Currently, the only option for protecting newborns at the highest risk of hospitalization (those born very prematurely, born with heart or lung conditions, or those born in remote communities without quick access to medical care) is a monoclonal antibody therapy called palivizumab. This drug can’t treat RSV, but if injected every month during RSV season, it can help prevent severe illness.

The problem is that palivizumab comes with a high price tag and needs to be administered every month, sometimes for up to six months, so it is typically reserved for high-risk infants. Health Canada recently approved a longer-acting antibody-based drug, nirsevimab, which would only require one injection per RSV season. Nirsevimab is expected to cost much less than palivizumab, and it may eventually be an option for all parents.

A vaccine for pregnant people to help protect newborns from infection is also in the pipeline and may be approved as soon as later this year. The vaccine, recently approved in the U.S. for older adults, offers the prospect of protection against RSV infection – not just disease – to all newborns for the first time. This RSV vaccine, made by Pfizer and known as RSVpreF, would be given to individuals in their late second or third trimester of pregnancy. The vaccine prompts the pregnant person to makes antibodies that are transferred to their fetus, so their child is born with some protection against RSV. In a worldwide, double-blind clinical trial with pregnant women published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the RSVpreF vaccine was more than 81 percent effective at protecting infants against serious health issues caused by RSV, like lower respiratory tract illness.

Speaking with parents about RSV and immunizations

Assistant professor Tiffany Fitzpatrick

In advance of the roll out of nirsevimab and Health Canada’s consideration of RSVpreF data, Fitzpatrick is listening to parents and learning about their understanding of RSV and potential concerns. Her research will involve conducting interviews with parents across Canada and using the information to create tailored educational materials that address questions and provide the information parents may need as they consider their future RSV immunization options.

“We need to start planning now to make sure that parents are anticipating this, and they have the information they need to be able to make that decision,” she says.

In addition to surveys and interviews, Fitzpatrick and her collaborators will be engaging with populations more vulnerable to RSV. For instance, research indicates that certain living conditions can play a role in a child’s risk for RSV. “We know if a child is exposed to mold, if they live in a crowded house, they’re much more likely to catch any respiratory virus and for it to become a much more severe disease,” says Fitzpatrick.

Specific regions and demographics are also disproportionately impacted by RSV. Collaborators on Fitzpatrick’s study will focus on parents in Nunavut — an area that has the highest rates of RSV hospitalization in the world. “They’re going to be working with community partners there to understand the unique barriers and motivators for RSV immunization in Inuit communities,” she says.

Fitzpatrick is aiming to have the educational materials from her study available in time for next year’s RSV season, when vaccines for pregnant people and nirsevimab will hopefully both be available.

“I hope this research provides parents the information that they need to make the decision that’s right for them,” she says. That said, as a public health practitioner, she ultimately hopes people decide to get immunized, “so we can prevent as much RSV disease as possible.”