Out of the Archives: Public Health Siblings, Donald and Frieda Fraser

January 26/2023

“Public Health Siblings; Donald and Frieda Fraser: Profiles From the Public Health History Archives, University of Toronto”

By Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D.

Professional Medical & Public Health Historian

Adjunct Professor, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto

Exploring the history of public health is not just about examining, understanding, and learning about past events and the successes and failures and the people responsible for both. It is also a pragmatic initiative, as much about connecting and relating those past events, successes, failures, and people, with the present challenges of public health and helping shape its future. A valuable window into the history of public health, particularly through the lens of individuals connected with public health research, teaching, and public service at, or associated with, the University of Toronto, is available through a broad range of personal/professional collections held in the University of Toronto Archives.

This is the first in a series of articles that will focus on selected collections (or “fonds) of documents, records, photos, and other materials one can discover and explore after entering “public health” into the University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services (UTARMS) website search engine.

https://utarms.library.utoronto.ca/

From left to right, Dr. Donald T. Fraser and Dr. Frieda H. Fraser, with R.C. Parker and R.D. Defries at the School of Hygiene, c. 1940s.

Image: Archives, Sanofi Pasteur Canada (formerly Connaught Laboratories).

One of the most significant collections of public health focused professional and personal papers held in the U of T Archives is known as the “Fraser Family Records” (Accession B1995-0044).[1] This fonds includes over 8 metres of materials from three members of the Fraser family, William Henry Fraser (1853-1916), Donald Thomas Fraser (1888-1954), and Frieda Helen Fraser (1899-1994), along with Frieda’s lifetime companion, Edith (Bud) Bickerton Williams (1899-1979).

With respect to the history of public health, of particular interest in terms of amount and scope, are the materials from Frieda Fraser, and to a lesser degree, of her older brother, Donald Fraser. Records from their father, William Henry Fraser are part of the collection, but are not related to public health as he was a Professor of Italian and Spanish. However, of special interest, although less so with respect to public health directly, are the papers of Edith Williams, who was a veterinarian, and especially the extensive correspondence she had with Frieda that uniquely document their personal same-sex relationship. Indeed, the Frieda Fraser – Edith Williams correspondence has attracted considerable attention from historians interested in lesbian relationships during the 1920s through 1970s.[2]

The Fraser Family Records does not include a distinct collection of records from Donald Fraser, although Frieda’s papers include materials related to Donald. There is also a small Donald Fraser supplementary fonds (B97-0027) with materials related mostly to his WWI service.

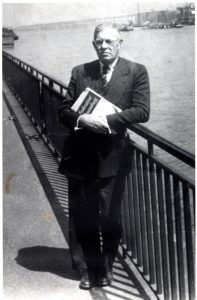

Donald T. Fraser was born in Toronto on September 27, 1888, and earned his BA in 1912, followed by a degree in

Dr. Donald T. Fraser, c. 1920s.

Image: Archives, Sanofi Pasteur Canada (formerly Connaught Laboratories).

medicine in 1915, both from the University of Toronto. He enlisted when World War I broke out and served in British Army field ambulance units in Egypt and France. In 1918, after further service in China, Fraser returned home, married, and joined the staff of the University of Toronto’s Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories as a bacteriologist and was soon appointed Assistant Director of the Labs. Fraser quickly became the third pillar in the Lab’s original leadership, along with Dr. John G. FitzGerald and Dr. Robert D. Defries.

Connaught was established in 1914 as the Antitoxin Laboratory of the Department of Hygiene, based in the U of T’s Medical Building. Fueled by wartime demand for tetanus antitoxin and smallpox vaccine, the labs soon grew to include a large farm property on Steeles Ave and Dufferin Street with expanded lab facilities. This unique, self-supporting, and public-service-based operation was officially named the Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories and University Farm in October 1917, and by 1920 operated independently under the Connaught Committee of the University of Toronto’s Board of Governors until 1972.[3]

In 1920, Donald Fraser also joined the staff of the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine of the Faculty of Medicine and would play a key role in the development of the School of Hygiene. The School formally opened in the new Hygiene Building in June 1927, which also accommodated expanded research and vaccine and insulin production facilities for Connaught. The School of Hygiene originally operated as the academic arm of Connaught, with the Labs’ proceeds supporting the School’s teaching and public health research mission. Connaught and the School had a shared administration under a shared director, the first of which was Dr. J.G. FitzGerald until his death in 1940, followed by Dr. R.D. Defries until 1955, when Connaught and the School were separated. The School of Hygiene then operated independently until 1975, when it was closed, with several of its departments integrated into the Faculty of Medicine’s Division of Community Medicine.[4]

Donald Fraser became a full professor in the School of Hygiene in 1932 and in 1940 became head of the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine following the death of Dr. FitzGerald. Fraser was a widely respected teacher and introduced the science of microbiology into the School’s curriculum. As a bacteriologist and immunologist, he was most interested in the prevention of tetanus, scarlet fever, pertussis (whooping cough), and especially diphtheria. Indeed, of his 49 papers published between 1920 and 1950, 27 dealt with aspects of the diphtheria problem.

Donald Fraser possessed a courageous spirit fed by a powerful drive to stand by his convictions and to prove, through the boldest of measures, the value of the biological health products he helped develop. Fraser, along with his family, often lent their services as human guinea pigs — including being among the first recipients of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids — a fearless undertaking that earned them legendary status at Connaught and the School. This dedication of both mind and body gave Fraser the confidence to speak publicly about the merits of immunization, opening many doors for the broader use of vaccines.

His courage and commitment to public health led Donald Fraser to undertake an extensive South American tour of

medical and public health schools despite a recent heart attack. Although he seemed recovered, a second heart attack struck on July 9, 1954, while he was in Santiago, Chile, resulting in his death ten days later. His legacy has continued with the “Donald Fraser Memorial Lecture” series launched by the Canadian Public Health Association in 1960, with the first lecture about his life and work.[5]

It is in his work primarily as a researcher that Donald Fraser appears in the “Fraser Family Records” through correspondence and research files that were assembled by his sister, Frieda, over some 40 years. Of particular interest in the collection are documents and correspondence that date from the time of Donald’s sudden death and the subsequent planning for the first Donald Fraser Memorial Lecture, which provide some valuable insights into his life and work. For example, Frieda was asked about whether her brother’s most important contribution was in teaching or research. “In trying to choose between teaching and research as Don’s most important contribution to the Connaught and the School, I keep coming back to the view that is neither one, but rather their inseparability or the balance between them.” She also noted that “Don’s medical experience was minimal – not even an internship. I doubt that he ever thought seriously of practicing. He was more impressed by what could be prevented than cured.”[6]

Many of Donald Fraser’s research and teaching interests in bacteriology, immunology and public health were matched and further developed by Frieda, as is well represented in the “Fraser Family Records.”

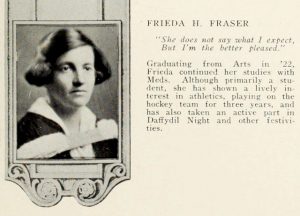

Frieda Helen Fraser was born in Toronto on August 30, 1899, and educated at home until age 15, when she spent 1914-17 at Havergal College, an independent day and boarding school for girls in Toronto. In September 1917, Frieda entered University College at the University of Toronto, earning a BA in 1922, specializing in physics and biology, after which she entered medical school at U of T. She completed her MB degree in 1925 and then moved to New York City, where she worked as an intern and resident at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children during 1925-26. Frieda next moved to Philadelphia to complete her post-doctoral training at the Henry Phipps Institute of the University of Pennsylvania, where she focused on chest diseases, especially tuberculosis, with Dr. Muriel McPhedran.

In 1927, Frieda returned to Toronto to work as a research assistant at Connaught Labs and a demonstrator in the School of Hygiene’s Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine. In 1928, she was promoted to research associate at Connaught, but with her work there demanding most of her time, Frieda reduced her demonstrator duties to part-time in 1929. In 1933, she was promoted to part-time lecturer in the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, to full-time in 1934, then assistant professor in 1936, and finally full professor in 1949. As Associate Professor of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine, Frieda taught bacteriology and preventive medicine to medical students, and to undergraduate and graduate students in public health nursing. In 1955 she was appointed professor of microbiology and retired from the university in 1965.

Bacteriology, and especially streptococcus, was the primary focus of Frieda Fraser’s research work at Connaught, and the development, production and testing of scarlet fever toxin, antitoxin, and toxoid.[7] She contributed to several scarlet fever related studies during the 1930s, including one that spanned four years (1934-38), titled “Streptococcal infection at the Preventorium,” which demonstrated that formalized scarlet fever toxin (scarlet fever toxoid) was ineffective for immunization, in contrast to diphtheria toxoid. Frieda also led a streptococcal infection study at Riverdale Isolation Hospital in 1940 and a study of streptococcal infection among Royal Canadian Air Force recruits in 1941-43.

In 1943, as Connaught began a major wartime penicillin development and production initiative for the Canadian government, Frieda participated in several penicillin studies. This work included research on the effect of intramuscular sodium penicillin (1943-44), the effect of oral penicillin (1944-46), the effect of intramuscular penicillin in oil and wax (1945-47), the use of crystalline penicillin on gonorrhea and syphilis (1948-49), and a study of newer preparations of penicillin for sustained action (1949-52). She was also involved in studies of several other antibiotics that continued into the early 1950s, followed by virus studies (1954-59) focused on the electrophoresis of viruses designed for purifying vaccinia virus. She then conducted research focused on clinical trials of phenoxalid in the treatment of tuberculosis (1959-61). Frieda worked closely with her brother, particularly on the streptococcus studies, and after his death, continued a special research project focused on developing an antigen for tuberculosis.

As is clear in the “Fraser Family Records,” Frieda kept a considerable amount of her files, notebooks and correspondence related to her research work at Connaught and the publications she wrote or co-wrote. She also kept files related to her teaching at the School of Hygiene, as well as administrative matters related to the School with which she would become more involved. Her files also include correspondence regarding her appointments and promotions at Connaught and the School, through which her salaries can be tracked over time. For example, as of July 1, 1949, Frieda earned $1,600 per year when she was promoted to Professor in the Department of Hygiene and Preventive Medicine. Also, as of April 1, 1951, Frieda also earned a salary of $4,000 per year as Research Associate at Connaught, which included one month of paid leave of absence per year. By July 1955, Frieda’s annual salary from Connaught had risen to $5,590.[8]

Such administrative records provide a valuable window into the history of Connaught and especially the School of Hygiene, particularly after it was separated from Connaught in 1955. Starting in 1956, the School of Hygiene had its own Director, the first of which was Dr. Andrew J. Rhodes (1956-1970),[9] and it was governed by its own School of Hygiene Council. Shortly after Rhodes became Director of the School, he approached Frieda about joining the new Department of Microbiology, which was to be established following the dissolving of the Department of Preventive Medicine and the creation of a new Department of Public Health. Frieda was happy to join the new Department of Microbiology, noting to Rhodes that “in general my interests have always been closer to the field of microbiology than to phases of preventive medicine from which microbiology is excluded.” At the same time, Connaught’s new Director, Dr. J.K.W Ferguson “has asked those of us who are associated with the Connaught whether we wish to retain our appointment in addition to our new commitments in the School of Hygiene. In view of the many years I have been on the staff of the Connaught, my answer was that I wish to remain so.” As she said to Rhodes, “I trust this is in accordance with your plans.”[10] Rhodes was agreeable and as of July 1, 1956, as Professor in the School’s Department of Microbiology, Frieda earned a salary of $8,050 per year.

Frieda’s files also provide a window into the world of women faculty members of the University of Toronto, of which there were limited numbers during the period when she was most active. Among the items in her files are a one-page listing of the members of the U of T Women’s Faculty Union in the mid-1950s, of which there were about 90.[11] Frieda was one of three women on the list with appointments with Connaught and the School of Hygiene (the others were Leone N. Farrell and Helen C. Plummer), and two with appointments at Connaught (Hilda M.G. Macmorine, and Edith Taylor, who also held an appointment in Chemistry). Also, among this list of 90 women faculty members, 8 held appointments in medically oriented departments, with one each in Anatomy, Physiology, Psychiatry, Pharmacy, Health Service, as well as Epidemiology, and two in the Banting & Best Department of Medical Research.

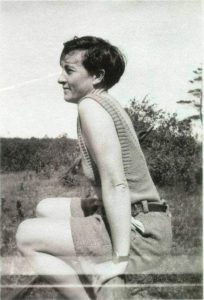

Frieda H Fraser and Edith Bickerton Williams, Wabitongushi Lake, 1936.

Image: University of Toronto Archives, B1995-0044, Box 009P.

As mentioned, Frieda’s files include correspondence, and most notably, letters she received from Edith Bickerton “Bud” Williams, during the mid-1920s through the end of the 1930s, when they began to live together in a house they shared near Burlington, ON. Most of the letters from Bud to Frieda date from between 1925 and 1942 and cover all aspects of their lives, including each of their relationships with their families and friends and how Frieda and Bud’s same-sex relationship was perceived. When they were apart, Frieda and Bud wrote to each other frequently, often daily and sometimes more than once a day. The collection of materials from Edith Bickerton “Bud” Williams in the “Fraser Family Records” consists mainly of correspondence, especially letters Bud received from Frieda dating from 1924 to 1942, with most written before the end of 1927. There are also letters Bud received just before 1976, when she suffered her first stroke and between then and her death in 1979; during this period, as Bud was unable to write, Frieda answered them.

Edith Bickerton “Bud” Williams was two months older than Frieda, born on June 24, 1899, in Toronto, and spent ten years at a private school for girls known as “Glen Mawr,” after which, in 1916, she entered University College at the University of Toronto as an Arts student. However, she was not inspired by the program and ended up failing after her second year. In 1925, she moved to Britain to work in a bank, but soon her mother could not prevent her from returning to Canada in 1927. She lived in Aurora, ON, for about ten years, raising poultry before she decided to enter the Ontario Veterinary College in Guelph. In 1941, Bud became the second woman in Ontario to graduate, after which she set up her own veterinary practice in Toronto at 675 St. Clair Ave. West.

Edith Bickerton “Bud” Williams, graduation photo, Ontario Veterinary College, 1941.

University of Toronto Archives, B1995-0044, Box 015P.

Bud and Frieda first met as children and became friends, although they went to different schools. However, once they both attended University College at U of T, their friendship grew into a closer, romantic, relationship that would last until Bud’s death in 1976. As noted, Frieda and Bud’s same-sex relationship as revealed through their extensive correspondence preserved in the “Fraser Family Records” collection, has been the focus of several articles, as well as a Ph.D. thesis.[12] However, as Frieda’s research and teaching in bacteriology and public health at the School of Hygiene and Connaught Labs were of limited interest to the authors of these works, it is uncertain how much their correspondence refer to Frieda’s work and the people she worked with. It would thus be a worthwhile initiative to closely review this correspondence collection with this in mind.

The ”Fraser Family Records” collection held the University of Toronto Archives is an especially rich resource of documentation related to the development of public health teaching and biotechnology research at the University of Toronto from the 1920s through the mid-1960s that took place in Connaught Laboratories and the School of Hygiene. The public health siblings of Donald and Frieda Fraser were each closely involved with Connaught and the School and the materials in the “Fraser Family Records,” especially from Frieda, provide a unique window into a particularly productive and dynamic period in the history of public health in Canada.

[1] https://discoverarchives.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/fraser-family-fonds

[2] Elisa Kukla, “Love at the sorority: Frieda and Edith were together most of the century,” Xtra, February 21, 2001, https://xtramagazine.com/love-sex/love-at-the-sorority-46423; Katherine Perdue, “Passion and Profession, Doctors in Skirts: The Letters of Doctors Frieda Fraser and Edith Bickerton Williams,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 22 (2) (2005): 271-80, https://utpjournals.press/doi/abs/10.3138/cbmh.22.2.271; Cameron Duder, “‘Two Middle-Aged and Very Good Looking Females That Spend All Their Week-Ends Together’: Female Professors and Same-Sex Relationships in Canada, 1910–1950” in Historical Identities: The Professoriate in Canada, E. Lisa Panayotidis and Paul Sortz (eds.), (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), p. 343-61; Katherine Anne Perdue, “Writing Desire: The Love Letters of Frieda Fraser and Edith Williams; Correspondence and Lesbian Subjectivity in Early Twentieth Century Canada,” Ph.D. Thesis, Department of History, York University, June 2014, https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10315/28211/Perdue_Katherine__A_2014_PhD.pdf; David Wencer, “Historicist: A ‘System of Partnership’ That Lasted a Lifetime,” Torontoist, June 18, 2016, https://torontoist.com/2016/06/historicist-frieda-bud/.

[3] The history of Connaught Laboratories while it was a self-supporting, public-service-based part of the University of Toronto (1914-1972) is documented in a series of 12 articles I prepared for the University of Toronto Connaught Fund website in 2018, https://connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history. See also the Sanofi Pasteur Canada “Legacy Project” website, http://thelegacyproject.ca.

[4] For an overview of the history of public health at the University of Toronto, see Christopher J. Rutty, “Within Reach of Everyone: The Birth. Maturity and Renewal of Public Health and the University of Toronto,” https://www.dlsph.utoronto.ca/history/. See also: Paul Bator with Andrew J. Rhodes, Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories, Volume 1, 1927-1955 (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1990), and Paul Bator, Within Reach of Everyone: A History of the University of Toronto School of Hygiene and the Connaught Laboratories Limited, Volume 2, 1955-1975; With An Update to the 1990s (Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association, 1995).

[5] G.D.W. Cameron, “The First Donald Fraser Memorial Lecture,” Canadian Journal of Public Health 51 (9) (Sept. 1960): 341-48, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41980923. For more about Dr. Donald Fraser, see his Biographical File held in the Archives of Sanofi Vaccines Toronto (formerly Connaught Laboratories); contact Christopher Rutty (who provides historical services to Sanofi Vaccines), hhrs@healthheritageresearch.com.

[6] Frieda Fraser to G.D.W. Cameron, undated letter (c. Feb. 1960), in reply to G.D.W. Cameron to Frieda Fraser, Jan. 28, 1960, University of Toronto Archives, B95-0044, Box 11, file 01 (Correspondence, 1960, 1963).

[7] For additional details about Frieda Fraser’s work at Connaught Laboratories, see her Biographical File held in the Archives of Sanofi Vaccines Toronto (formerly Connaught Laboratories); contact Christopher Rutty (who provides historical services to Sanofi Vaccines), hhrs@healthheritageresearch.com.

[8] University of Toronto Archives, B95-0044, Box 13, file 01 (Correspondence re. employment, U. of T., 1946-1966).

[9] Andrew J. Rhodes fonds, University of Toronto Archives, B2000-0001, https://discoverarchives.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/andrew-james-rhodes-fonds.

[10] Frieda Fraser to Andrew J. Rhodes, June 1, 1956, University of Toronto Archives, B95-0044, Box 13, file 01 (Correspondence re. employment, U. of T., 1946-1966).

[11] University of Toronto Archives, B95-0044, Box 14, file 01 (U. of T. Women’s Faculty Union).

[12] See Footnote #2.